3.1 - Capturing tweets for psychological analysis

By Christian Ryan

October 7, 2021

It has been a while since my last blog post - I got a bit distracted writing a book about R…

This blog post will be the first in a short series on using sentiment analysis with twitter data. When Covid-19 first started to affect Ireland, back in March 2019, a few colleagues and I were discussing the apparent differences in attitudes between countries towards the collective action required to enforce lockdowns and social distancing - particularly viewing these differences through the lens of Fisk’s relational models theory (1992).

Though the discussions didn’t lead to a research paper (we all got sidelined by other projects during lockdown), it did inspire me enough to do some regular twitter downloading, creating a database of tweets during that period from four different locations of interest to our group - Ireland, England, New York, Los Angeles. I used the package rtweet to access the tweets.

In this first post, we will look at the basics of downloading tweets using this package, before examining some of the text analytic tools for investigating the tweets themselves, in later posts.

rtweet setup

Firstly, you do need to create a token for use with the rtweet package, and this requires registering on the Twitter developers site here:

https://developer.twitter.com/en

It will allow you to create specific account credentials associated with your twitter account. You will use these at the start of the first R session using rtweet package to authentic your access to the Twitter API. However, this is a one-time-only requirement, and the token will be stored in RStudio from then on.

Once you set up a developer account, you will be given four pieces of information that it is important to record:

- consumer key

- consumer secret

- access token

- access secret

After loading the rtweet package, you will need to paste these into the create_token() function with the appropriate arguments. It should look something like this:

library(rtweet)

create_token(

app = "name_of_project",

consumer_key = "itWetc..etc",

consumer_secret = "S8teki9dta...etc",

access_token = "2313tcTdga...etc",

access_secret = "JBUuFuta...etc")

You can give the app argument any name you choose, but the long alphanumeric strings for the consumer key, consumer secret, access token and access secret must all be carefully copied from the Twitter developer site.

There is a very clear vignette on this process on the CRAN page for rtweet:

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rtweet/vignettes/auth.html

Once you have run the create_token() function, we can start a new RMarkdown script, load the rtweet package and run a quick search.

“Covid” as search term

library(tidyverse)

library(rtweet)

To demonstrate the search_tweets() function, let’s run a search with the word “covid” and see what we get. We pass the search term we are interested in as the “q” (query) argument. We include the number of tweets we want back. The limit in a single search is 18,000, but we can set the function to keep trying by setting the “retryonratelimit” argument to TRUE, then set the number of tweets to download higher than 18,000. With “retryonratelimit = TRUE”, it would potentially return 36,000 tweets if we set it to “n = 36000”, but the processing time for even one run to this maximum of 18,000 is not inconsiderable. Running a quick test, I found a single maximum search took 2 min 18 secs on my machine. However, if you exceed the 18,000 search limit, the programme waits for 15 minutes before it can run the retry. So you can imagine that the search time will quickly escalate if you enter anything more than the maximum value. When I wanted to download large samples, I set the n to some large value such as 200,000 but did not run the code chunk until I had finished on my computer for the night. Usually, this works effectively, but I did find occasionally the process might crash after 3 or 4 retries, but this still netted 54,000 - 72,000 tweets.

You can also specify which language the tweets are written in: we will pick English here (en).

df <- search_tweets(q="covid",

n = 100,

lang = "en")

If you look in the environment pane of RStudio after you run this code, you will notice that we get our tweets back as a dataframe with an observation for each tweet, but the tweets come with 89 other variables, including some useful ones such as created_at (date/time), screen_name, and retweet_count. But as there are so many variables, we can run some select() and head() functions to have a quick scan of the data before we dig any deeper.

df %>%

select(screen_name, text, retweet_count) %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## screen_name text retweet_count

## <chr> <chr> <int>

## 1 Fionaroha "If you are part of the new Covid teams going into … 348

## 2 4evrmomof4 "Anti-Muslim Republican congressional candidate Lau… 306

## 3 4evrmomof4 "Far right Republican Laura Loomer has a bad case o… 1937

## 4 rajesh_dce "Today when Modi Govt is working hard for world rec… 10

## 5 MLeeBaxter1 "Don Lemon and Joy Reid are right. How can you poss… 161

## 6 notibrahym "@arslayyy 3 NZ players are covid +ve 😕" 0

Here we can see the first six tweets, with the screen_name, the text of the tweet and the retweet_count. If we want to see which tweets are the strongest trending, we could use arrange(desc()) on the retweet_count variable. We can use slice() to select the top 5 tweets and then pull out just the text of the tweets.

df %>%

arrange(desc(retweet_count)) %>%

slice(1:5) %>%

pull(text)

## [1] "someone saw me doing wudhu at work and said \"you must be really paranoid about covid\" im paranoid about qiyamat sir"

## [2] "NIH now recommends Vitamin C, D3 and Zinc for prevention and treatment of Covid-19. The rest of us who have recommended it for the past 18 months don't even want an apology."

## [3] "We're having trouble flattening the COVID-19 curve because we can't flatten the stupidity curve."

## [4] "BREAKING NEWS: Los Angeles announces that it will begin requiring proof of COVID vaccination at bars and other nightlife destinations. RT IF YOU THINK THAT EVERY CITY IN AMERICA SHOULD DO THE SAME!"

## [5] "If you are not absolutely HORRIFIED by the war-like COVID-19 casualties in Ron DeSantis' botched pandemic response, you're either numb or not paying attention.\n\nNeither is acceptable.\n#FloridaIsVietnam https://t.co/QdOE1OeWED"

As might be expected when searching for tweets about a socially divisive and polarising issue such as a pandemic, many contain hyperbole and no small amount of drôle humour - “I am paranoid about qiyamat”!

This first strategy has given us a sample of tweets from the twitter api, but we have only searched using a keyword (“covid”). We can narrow our search by including a location and a radius within which to search, which allows us to sample by a specific geographic region.

Location using geocode

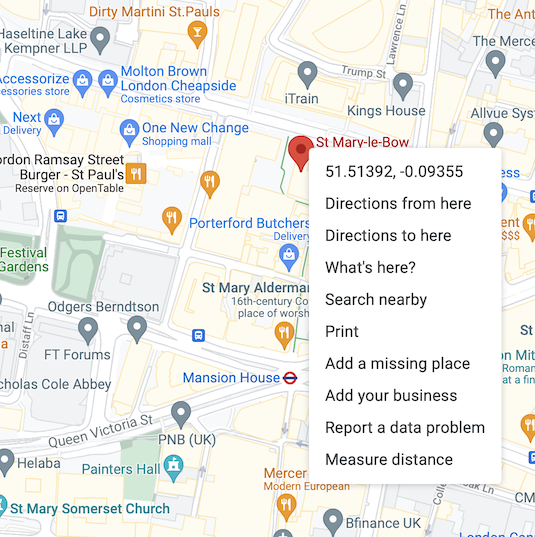

To specify a location, we use the geocode argument. I found the syntax for this slightly counter-intuitive. You must pass the location as a string, using commas to separate the three elements - latitude, longitude and radius. However, you need to be careful to avoid any whitespace in the string. So if you pass “52.68, -7.81, 120 mi”, it will return an error because of the three whitespaces in this string. Getting the geocode for your target location is easy with google maps. Say we wanted to pick Bow Bells in London - after entering the name into the search bar, Google maps will show the relevant area with a red pin to mark the location identified. If you right-click over the pin, it will reveal the latitude and longitude of that location in the first line of the drop-down list.

We can see that Bow Bells is at 51.51392, -0.09355. To create our geocode argument, we include these two figures with a chosen radius. Say we want a 50-mile radius of Bow Bells to take in much of Greater London - we would pass the following string as the geocode argument: “51.51392,-0.09355,50mi”. As we are only experimenting with the rtweet package, I will over-write the ‘df’ dataframe with this new search rather than create a new dataframe.

df <- search_tweets(q = "covid",

n = 100,

lang = "en",

geocode = "51.51392,-0.09355,50mi")

Obviously, if you run this code for yourself, you will get a different set of tweets, dependent on the day and time that you run the search. If you would like to follow along with my code and see the impact on the very same tweets, I have stored this dataset as “london” in the r4psych package that I created to accompany my book. To get the data, you can follow these steps. We use devtools to install the package, because it isn’t on CRAN, but github instead. Then we load the package, call the dataset with data(), and rename it to df.

library(devtools)

install_github("Christian-Ryan/r4psych")

library(r4psych)

data(london)

df <- london

rm(london)

Let’s take a quick look at the text of the first 5 tweets from the London area on the topic of “covid”.

df %>%

slice(1:5) %>%

pull(text)

## [1] "Many more applied for EU citizenship on the basis of their heritage, and some, no doubt, are only tying loose ends before making the move. \n\nThey don't do it because of covid, they do it because of brexit. \n\nCovid will fade out, eventually. \n\nHowever, we're stuck with brexit."

## [2] "Is there really a question whether it's covid or brexit that's breaking UK economy? \n\nAll essential businesses were open throughout lockdown. Millions worked from home. \n\nPeople who died, who of course are sadly missed, were mostly retired. They didn't work anyway."

## [3] "@ohsouthlondon @CPFC Depends whats written in the contract and IF it is related to the pandemic. They vendor would have entered into the contract knowing the risks at the time.. To many blaming covid for poor service. If you take on a contract you deliver or face penalties"

## [4] "@leoniedelt I did a covid test yesterday at home just to make sure I’m healthy as I have a busy weekend. I’ve just got a cold. Our immune systems aren’t strong due to being locked in maybe that’s why there are so many deaths happening now?"

## [5] "@Jim936 For me it’s been the “post grouping” anxiety. In the moment I am fine (alcohol probably helped that at clubs etc) but the next few days are spent convincing myself I’ve got covid and so I wonder if it’s worth it, but it always is at the time, just not so much afterwards"

Perhaps unsurprisingly, two of the five London covid tweets refer to Brexit - which suggests the geocode is doing its job!

Cleaning the tweets - “smart quotes”

You may have noticed that the tweets include some symbols that may be unfamiliar, such as the new line symbol “\n”, as well as other symbols such as emojis, that may need processing as we carry out a text analysis. However, there is one type of symbol in the tweets that can cause difficulty for many of the text processing functions that we want to use, and it is the so-called smart quotation mark. See, for example, the quotation marks around “post grouping” in the fifth tweet above. These are directional quotation marks that take a different shape depending on whether they are opening quotes or closing quotes. Here is an example of smart quotation marks:

These can cause problems for some R functions that rely on straight quotation marks like these:

So before we make any other changes to our tweet text, we should convert all of the directional quotation marks (and apostrophes) to straight marks. Luckily, the package proustr has a function that will do just this (see the next blog post for an alternative method using textclean!). If you have this package installed, you can skip the next step. If not, we will run the install.packages() function with the package name, then load the package with library().

install.packages("proustr")

library(proustr)

The proustr package contains a range of tools for working with the original French texts of Marcel Proust’s “A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu”. But for us, the benefit is a function called pr_normalize_punc() which converts smart quotation marks to straight ones. To see how this works, let’s create a short text in a tibble containing smart quotation marks. The reason for creating a dataframe is that this is the kind of data object that pr_normalise_punc() is expecting.

smart_quotes <- tibble(text = "A “smart quotation” in a short text")

smart_quotes$text

## [1] "A “smart quotation” in a short text"

It is harder to see in the HTML output from RStudio, but if you look closely at the output above, you will see that the opening and closing quotation marks around the words ‘smart quotation’ are slanted and differ both to each other and to the straight quotation marks that indicate the start and end of the entire string.

The pr_normalise_punc() function takes two arguments: the name of the data frame and the name of the variable with text to be normalised - in our case, this is ‘smart_quotes’ and ‘text’.

pr_normalize_punc(smart_quotes, text)

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## text

## * <chr>

## 1 "A \"smart quotation\" in a short text"

We can see also that the object it returns is also a tibble, which will allow us to use this function seamlessly with the pipe. The key change in the string is that the quotation marks have been replaced with straight marks (in HTML on this website, they also have escape characters before each of them, as the output as a text string already uses straight quotation marks to indicate the start and end of the text string). We can now use the pipe to demonstrate how to overwrite our original file with the new punctuation-corrected text variable.

smart_quotes <- smart_quotes %>%

pr_normalize_punc(text)

smart_quotes

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## text

## * <chr>

## 1 "A \"smart quotation\" in a short text"

The pr_normalize_punc() function works seamlessly with the tidyverse tools, and we don’t even need to embed the change inside a mutate() function. Now we have seen how this function works, let’s apply it to our twitter dataset.

df <- df %>%

pr_normalize_punc(text)

Convert emojis to text

We have fixed the problematic punctuation marks, so let’s move on to address the emojis. To see how emojis are rendered, we can look at a text by user 2800537807, using a filter() and pull() sequence.

df %>%

filter(user_id == "2800537807") %>%

pull(text)

## [1] "@MailOnline Nice 👍😁 so when Pfizer will recall \"covid-19\" vaccines?! Oh sorry its making to much money for Pfizer shareholders probably never! Just keep \"boost jabs\" in arm 😉 and all will be fine! If you die of side effects of jab no problem! Its UK and USA approved! So good luck 👍😉"

In this tweet, we see that five emojis are used. If some twitter users express emotion through emojis rather than words, we may judge that we need a way to capture this sentiment, rather than simply screen out emojis and non-linguistic characters. One option is to convert each emoji to a character representation. We can do this with a function from the textclean package.

library(textclean)

We can pass our tweet to the replace_emoji() function. Note that it is expecting a string vector, so we need to use the pull() function to pull the variable out of the dataframe before passing it to the replace_emoji() function with the dot syntax.

df %>%

filter(user_id == "2800537807") %>%

pull(text) %>%

replace_emoji(.)

## [1] "@MailOnline Nice thumbs up beaming face with smiling eyes so when Pfizer will recall \"covid-19\" vaccines?! Oh sorry its making to much money for Pfizer shareholders probably never! Just keep \"boost jabs\" in arm winking face and all will be fine! If you die of side effects of jab no problem! Its UK and USA approved! So good luck thumbs up winking face "

Here we see that the function replaces the emojis with the character equivalent, such as “thumbs up” and “beaming face with smiling eyes”. Notice that it does not include any punctuation but places the text directly in line with the rest of the tweet. This would allow us to search the corpus as a whole for the phrase “thumbs up”, and we might expect that this will usually have been represented by an emoji in the original tweets rather than this particular character string. We might also want to think about the emotionally equivalent phrase, as “thumbs up” describes the physical gesture, but we might regard it as meaning “okay”, “all good”, or some other affect-related term, indicating approval or assent.

Characters that are not converted to text

I saved the original london tweets data as “london.Rdata” before running the punctuation correction code block. So, to demonstrate what would have happened if we had tried to convert the emojis without fixing our smart quotation marks, I will reload the dataset, run the replace_emoji() function and show you the output.

load("london.Rdata")

london %>%

filter(user_id == "2800537807") %>%

pull(text) %>%

replace_emoji(.)

## [1] "@MailOnline Nice thumbs up beaming face with smiling eyes so when Pfizer will recall <e2><80><9c>covid-19<e2><80><9d> vaccines?! Oh sorry its making to much money for Pfizer shareholders probably never! Just keep <e2><80><9c>boost jabs<e2><80><9d> in arm winking face and all will be fine! If you die of side effects of jab no problem! Its UK and USA approved! So good luck thumbs up winking face "

Here we see that the smart quotation marks were converted to the code: (<e2><80><9c>) and (<e2><80><9d>). This is because one of the behaviours of the replace_emoji() function is to coerce all of the text into ASCII, so some elements of punctuation or emojis that it does not recognise get converted into UTF-8 hexadecimal codes. We will look at these other codes in a bit more detail later. However, I think it is easier to do the conversion first rather than have to work with the hexadecimal codes.

We should note that so far, we extracted an individual tweet with emoji characters, pulled out the text variable and converted it. But what if we want to apply replace_emoji() function to the whole of our dataframe and overwrite the results in the text variable? To do this, we can use the replace function inside a mutate() function and over-write our text variable.

df <- df %>%

mutate(text = replace_emoji(text))

Contractions

We may want to do some word counting in our text analysis, and contractions will skew our results, being treated as one rather than two words. The textclean package also has a function to fix this. If we look at the fourth tweet in the london dataframe, by someone with the screen_name “rosie_dodds”, we can see the contractions “I’m”, “I’ve”, “aren’t”, and “that’s”.

df %>%

filter(screen_name == "rosie_dodds") %>%

pull("text")

## [1] "@leoniedelt I did a covid test yesterday at home just to make sure I'm healthy as I have a busy weekend. I've just got a cold. Our immune systems aren't strong due to being locked in maybe that's why there are so many deaths happening now?"

Let’s use the textclean package function called replace_contraction() that works the same way as replace_emoji().

df %>%

filter(screen_name == "rosie_dodds") %>%

pull(text) %>%

replace_contraction(.)

## [1] "@leoniedelt I did a covid test yesterday at home just to make sure I am healthy as I have a busy weekend. I have just got a cold. Our immune systems are not strong due to being locked in maybe that is why there are so many deaths happening now?"

We can see that this has worked effectively. We can also apply this to the whole dataset and over-write the results, just as we did with the replace_emoji() function.

df <- df %>%

mutate(text = replace_contraction(text))

It is important to be aware that this function can make mistakes. If we check the fifth tweet, we can see one.

df[5, "text"]

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## text

## <chr>

## 1 "@Jim936 For me it is been the \"post grouping\" anxiety. In the moment I am …

Here, the function has replaced “For me it’s been” with “it is” rather than “it has”. In this case, we may not be too concerned with this error as the function is only working on stopwords, and the count of stopwords will still be the same. But we would need to be more cautious if we were interested in the grammar or expressions used in tweets.

We have made some progress tidying up the text variable of our tweets. We might want to synthesise each of these individual steps into one chunk like this:

df <- df %>%

pr_normalize_punc(text) %>%

mutate(text = replace_emoji(text)) %>%

mutate(text = replace_contraction(text))

In the next blog post in this series, we will examine the use of tags, hash, HTML and URLs in tweets, in preparation for extracting sentiment using tidytext techniques and an emotion lexicon. If you want to follow along, I would suggest saving the dataset we have been altering, so that you can reload it later.

References

Fiske, A. P. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99(4), 689–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.689

- Posted on:

- October 7, 2021

- Length:

- 17 minute read, 3546 words

- See Also: